Bruno Lisi

Di lui hanno scritto, in occasione di varie “personali”, tra gli altri, Marisa Volpi, Carmine Benincasa, Francesco Moschini, Claudia Terenzi, Cesare Vivaldi.

La pittura come sollecitazione / La pittura come vibrazione

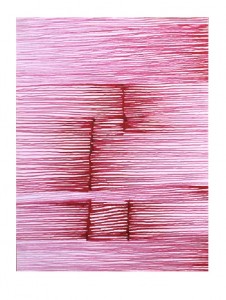

Abituati come eravamo alla puntigliosa meticolosità del “tutto pieno” dell’intero itinerario artistico di Bruno Lisi, è oggi davvero sorprendente vederlo impegnato in un nuovo ciclo che sembra avere come proprio fondamento l’abbacinante rarefazione del vuoto. A sottolineare poi questo apparente mutamento di indirizzo della propria ricerca egli ha fatto ricorso ad una tecnica e ad uno strumento come la penna a sfera, certo molto distanti dalla sua abituale predilezione per una pittura intrisa di vibranti pulsioni, proprio per la loro asetticità e per il loro alludere ad un universo indistinto ed indifferenziato. Ma si tratta, ancora una volta, per B.Lisi, di dar corpo a profondità inesplorate, di far uscire dalla superficie delle figure poste in tensione, come se l’intera opera fosse trattata “pittoricamente” e non solo quindi la parte dove il segno si ispessisce sino a farsi fasciante ed a trattenere l’urgenza di sotterranee vibrazioni.

Ecco perché togliendo ogni parvenza di automatismo al segno tracciato, B.Lisi impone allo stesso una sorta di chiaro-scurale sfumato che conferisce all’immagine fatta affiorare un vitalismo, un animismo ed una sorta di pampsichismo che sembra spingere la sua ricerca ad apparentarsi più con quelle teorie sull’universo come “brullichio” che non come pura aspirazione alla forma.

E’ quanto almeno sembrerebbe indicare certa sontuosità barocca lasciata intravedere dietro quei “sipari” annodati e alzati, quel cangiantismo materico alla “Ludovica Albertoni”, mosso dal vento, ma raggelato dal suo essere costretto ad affiorare appena, quasi scheletrica presenza sopravvissuta all’erosione del troppo vuoto che la circonda.

Non è un caso poi che appena evocate queste presenze, B. Lisi le abbia ritagliate e ricondotte in una sequenza verticale da vera e propria stele imprimendo all’intero montaggio, attraverso il nitore dei due fogli bianchi posti in successione, una voluta arcaicità che dichiarasse subito la propria distanza da possibili memorie di pittura-pittura. Tutto ciò per farsi più sofferta interrogazione sulla costruzione del vuoto, sulla struttura della figura che si rivela nel proprio negarsi, nell’abbandonico lasciarsi andare della mano che dà corpo e struttura senza un disegno a priori.

La stessa esasperazione dimensionale impressa dalla verticalità assunta dall’opera, quella costrizione a farsi puro cantuccio poetico nell’anomala collocazione in alto delle varie figurazioni, spiazzate nelle loro più diverse giaciture, sembrano misurare il vuoto abissale che le costringe a rapprendersi ed a rinchiudersi sempre più a bozzolo. Più che un veloce passaggio di nuvole allora, quelle apparizioni sembrano indicare un timore e nello stesso tempo un bisogno di prendere le distanze da quel vuoto che pure le ha fatte riaffiorare in una oscillazione continua tra voglia di immergervisi e timore di sprofondarvi. Il tutto, nella certezza però che il loro prorompere è garantito proprio dal ritrarsi di quel vuoto, dal suo aprirsi quasi a lasciare forre di accumulo d’ombra se non di mistero.

Ma, a sottolineare la sostanziale identità tra le figure affioranti, ridotte a simulacri se non a veri e propri reperti di uno scavo stratigrafico, quel vuoto incontaminato eppure sollecitato dalle leggere scosse telluriche che mettevano in vibrazione quegli stessi brandelli d’immagine, B.Lisi affianca alla rarefazione di questo ciclo una serrata sequenza di più labirintici segni.

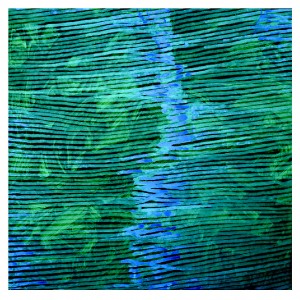

Una serie cioè di lavori in cui, più liberamente, il segno tracciato si sovrappone, si insegue, s’intreccia sino ad occupare ogni interstizio. Il tutto in una costrizione a rimanere nei limiti fisici del foglio, a non lasciare vuoti inesplorati, quasi a sottolineare la lontananza di questo modo di procedere dal fiducioso andare oltre, da quella voglia di trasbordare che era tipica invece, ad esempio, di J.Pollock. E questo chiudersi all’interno di una superficie misurata e controllabile, sforzandosi di farne affiorare impreviste profondità solo attraverso il cangiantismo del segno che si sovrappone, o il trascolorare dei diversi segni che si intrecciano, non può che ricondurci a quell’idea che, come ossessione continua, permea il lavoro di B.Lisi dagli anni sessanta ad oggi, quella cioè di una pittura intesa come sollecitazione continua se non come messa in vibrazione della superficie pittorica.

Ed è proprio questo lavoro in superficie, paradossalmente, a registrare quella ricerca di interiorità e di grande spiritualità che dalle avanguardie storiche in poi ha sempre caratterizzato il percorso verso l’astrazione. E sono proprio questi fogli, con la loro ossessione per un segno insistito e che torna sempre su se stesso con la propria circolarità, a richiamare quel naturalismo, da B.Lisi sempre invocato, come fondamento del proprio operare, alla ricerca di quel “continuum dove tutto è”.

Non è caso allora che, sottolineata la propria distanza di procedimento dall’espressionismo astratto americano, quello più fiducioso nelle “magnifiche sorti e progressive” dell’umanità, il lavoro di B.Lisi tenda invece a costruire una sorta di continuità con quei percorsi fatti di fittissime trame di microsegni vibranti attraverso cui M.Tobey esprimeva l’incessante pulsare della vita.

Che altro è quell’eccesso di pieno, contrapposto a quella vertigine del vuoto, se non un rammemorare a distanza quella “white writing”, quella scrittura bianca che, a parte l’ascendenza orientale di fondo, non può che presentarsi come momento conoscitivo se non di pura riflessione sul reale? Allo stesso modo, lo scrivere attraverso superfici ampie e luminose, come già è accaduto in altri suoi cicli pittorici, per B.Lisi, è come portare alla coscienza frammenti da lontano che l’artista si sforza di captare e di tradurre in un nuovo ordine che non sia quello intellettualistico e concettuale ma quello più vissuto del quotidiano che si fa proiezione continua del presente.

In una sorta di teatro delle ombre il prorompente apparire, per poi farsi evanescente, di un universo portato alla ribalta visiva, non fa che mantenerci nell’instabile equilibrio di precari spettatori di una scena che vorremmo oltrepassare e che siamo costretti invece a continuare a traguardare nella sua spiazzante e levigata profondità da stiacciato donatelliano. Ed è questa stessa riduzione ad una spazialità concentratissima a scandire il lavoro di B.Lisi fin dai suoi esordi nei primi anni sessanta. Fin da allora, il suo muoversi tra astrazione e figurazione, alla ricerca di un esito che lo collocasse al di fuori della ormai logora polemica tra astrattismo e realismo, vi aveva fatto individuare in alcuni artisti come ad esempio A.Magnelli un mondo espressivo di intense sollecitazioni proprio per il suo scommettere sull’astrazione di elementi ben definiti e di solida connotazione costruttiva. Ma anziché rileggere la portata teorica di quel maestro italiano dell’astrattismo in una declinazione esasperata di strutturalità geometrica, come già avevano fatto, sul finire degli anni quaranta, gli artisti di Forma 1, B.Lisi ne coglie più che la decontaminazione della pittura da qualsiasi ridondanza narrativa, le qualità della vibrazione pittorica. B.Lisi privilegia cioè ciò che in Afro si preciserà come pura struttura luminosa, sino a risolvere lui, artista pur così giovane in quegli anni, la dialettica tra materia e luce in un precario equilibrio tra i due termini.

E’ proprio a ridosso delle sue prime esperienze astratte l’incalzare dell’urgenza informale che lo porta ad esasperare colori di brume e di terra sino ad arrivare a fondi bituminosi che negano ogni affondo visivo. E’ in quegli stessi anni allora, che B.Lisi recupera attraverso il monumentalismo di alcune figure una spazialità di grande respiro in cui il giustapporsi di ampie stesure cromatiche si fa già allusione naturalistica, premonitrice di quegli sfondamenti spaziali che, sul finire degli anni sessanta, egli porterà a magistrale compimento evidenziandoli nella loro esasperata dilatazione e nella pur forzata costrizione del piccolo formato. In una sorta di esercizio di autocensura B.Lisi tende allora a raffreddare quanto di distruttivo potesse portare in sé la gestualità dell’operazione pittorica.

Il gesto, a stento frenato, costringe allora le figure colte a distanza ravvicinata, una parte del corpo soltanto, due mani, con una aspirazione all’indistinto, al non precisato, al non finito, ad esibire la propria condizione di frammenti, come se dipingere per B.Lisi significasse esaurire o meglio ancora bruciare in uno spazio ridottissimo ed in un tempo che non ammetteva mutamenti, né tantomeno delle riprese, la memorizzazione di un’impressione. L’artista sembrava allora teso a formare la velocità del passaggio dell’immagine in quel vuoto inteso come reale protagonista dell’opera più che a fissare l’immagine stessa. Giungeva così ad una fisicità di quel passaggio d’immagine in modo che il discorso scivolava dai dati oggettivi alle loro possibili deformazioni, dal dato reale alla sua manipolazione sulla via di una perseguita emblematicità che si fondava sulla ricerca di una stringente immediatezza, sulla folgorazione cromatica data per urlata contrapposizione di accesi colori. E che il lavoro di B.Lisi tendesse sempre più alla riduzione di qualsiasi presenza all’interno dell’opera, scarnificando il colore ed eliminando ogni struttura che potesse far pensare ad una ricercata complessità d’impostazione, sembrano ben dichiararlo i lavori successivi che tendono a fare del vuoto, del bianco della tela appena fatto vibrare, il luogo del minimo intervento, da muovere appena, da far increspare come una tavola di cera appena solcata o meglio appena attraversata da impronte-meteore di cui non si può che osservare la sola traccia.

Alla fine non resta allora che la malinconia per una vagheggiata perdita della cui mancanza non potranno che essere evocate tracce mute e silenziose che nel loro farsi uniformi e intoccabili, sottolineano il valore di pure comparse che la memoria sotterra e dissotterra con ossessiva insistenza. E’ così per le immagini-meteore di enfatizzate parti anatomiche, ma è così pure per le serrate “tensioni” elaborate da B.Lisi nella prima metà degli anni settanta.

E comincia proprio in questi anni una critica serrata da parte di un artista ai fondamenti stessi dell’opera per concentrarsi più sulla struttura della stessa che non sui dati che essa sembra voler comunicare all’esterno. Ma, si badi bene, non in termini tautologici come sembrava fare parallelamente la pittura aniconica, non cioè sugli stessi strumenti disciplinari, ma piuttosto sui fondamenti della visione, su quelle “strutture assenti” capaci però di determinare e legittimare storicamente l’opera d’arte. Per questo era necessaria una riduzione al grado zero della pittura, una riscoperta dei suoi valori primari, sino ad abbandonare il piacere stesso della pittura per pure stesure asettiche e rinunciatarie. Non è un caso allora che B.Lisi riscopra nell’azzeramento totale delle avanguardie sovietiche e di quelle formaliste in particolare, il fondamento delle sue nuove ricerche. Non solo il Quadrato nero su bianco di K.S.Malevic ma anche le stratificate sovrapposizioni monocrome di A.M. Rodcenko costituiranno certo il punto di riferimento per un nuovo modo di fare pittura che individua nella pura spazialità della superficie pittorica, non una sorta di tabula rasa su cui incidere e raccontare la propria visione del mondo, ma semmai e soltanto la non oggettività del mondo come sola finalità dell’opera, sino a dimostrare come non sia poi così reale la realtà “pratica” delle cose.

Tutto ciò in nome di una conoscenza pura e assoluta di ogni forma di oggettività, subordinando il colore e la struttura dell’opera ad una comunicazione spirituale e di pura idealizzazione. Val la pena allora rileggere quelle Tensioni più che nei loro dati di ambiguità, come già a suo tempo aveva evidenziato C.Vivaldi, nel loro aspetto costruttivo e ludico ad un tempo, quasi di geometrie della mente memori di quella primordialità costruttiva che da ragazzi ci faceva giocare con gli elastici tra le mani sino a farci scoprire complesse geometrie intercambiabili con una semplice operazione di ars combinatoria. Così quelle impronte quasi monocrome che solcavano appena la superficie pittorica, sino a farla vibrare per l’effetto di una brezza radente, alludevano ad una cosmologia del quotidiano di tenerissimo effetto pur nel loro eccesso di concentrazione se paragonate al “far grande” che si celava dietro il mito della nuova frontiera dei coevi grandi Cellotex di A.Burri. Ma quanto in A.Burri era decantazione solare della materia portata a nuova bellezza, in B.Lisi si evidenziava come ritagliata porzione di una spazialità volutamente limitata, ricondotta alla propria controllabilità e misurabilità quasi a non far vedere, oltre le possibili siepi, altri spazi ed altri silenzi. Ed è proprio questo l’aspetto che, a metà degli anni ottanta, verrà accentuato da B.Lisi in un acceso spiritualismo che, enfatizzando la centralità dell’opera in una sorta di propagazione cosmica della materia, costringe la stessa a disporsi secondo un respiro davvero cosmico.

La stessa fioritura che accompagna il dispiegarsi sinuoso di quelle onde di propagazione, sembra evidenziare lo stesso atto magico del creare. Nulla di più distante in questa messa a fuoco quasi al microscopio delle riprese “ravvicinate” di D.Gnoli nel loro enfatizzare la realtà per esorcizzarla, di queste calibrate lievitazioni, quasi la materia fermentasse tracciando scie luminose e facendo precipitare pulviscolo. Ma quel precipitare ha il sapore alchemico della trasmutazione della materia e certo è il segno dell’amorevole assecondamento che B.Lisi sembra operare con la propria azione maieutica nei confronti della materia stessa, sin quasi a costringerla ad esibire la propria bellezza folgorante con il suo smalto e la sua incisività, pur nella coscienza del suo inevitabile portare con sé i segni della propria distruzione. La stessa patinata bellezza sembra così uniformare le opere più recenti, che a partire dall’ ’86 B.Lisi ha impostato con un ciclo di quadri blu di straordinaria concatenazione ed emozionante respiro.

Nella prima serie, una sorta di inquadramento se non un vero e proprio boccascena ottenuto con una bordatura unitaria della tela, faceva irrompere in una sorta di ribalta ideale la magmatica esplosione di grumi di materia di viaria grandezza. Ma, nel contempo, l’esasperata frontalità del tutto alludeva ad una raggelata Isola dei morti di böckliniana memoria intaccata appena dalla corrosività e dall’irruenza di quei flutti o, che è lo stesso, dall’infittirsi incontrollato di un’aggressiva vegetazione. Eppure l’effetto finale restituiva la stessa impietosa durezza di un desertico paesaggio di C.D. Friedrich che, solo più recentemente, proprio negli ultimi lavori di B.Lisi, ha iniziato ad ammorbidirsi, nella serie “millimitrata” di paesaggi scanditi dal giustapporsi come tessere in un ideale mosaico.

E’ qui che si dispiega in tutta la sua vitalità la passione dell’artista per l’affresco che per un po’ di anni egli ha avuto modo di conoscere come restauratore, e come successione di giornate possono intendersi allora i montaggi di quelle maglie in cui la materia si espande, si estende e si enfatizza quasi a denunciare che la sua bellezza può essere per lo meno fissata dall’amore stesso per le cose pur scoprendo in esse e svelando simultaneamente e perfidamente il vuoto abissale in cui potremmo essere precipitati se ci bastasse quell’estenuante bellezza da “sepolcro imbiancato” e non ci sorreggesse invece quell’eterna tensione verso l’altrove.

Bruno Lisi, artist of sign, was the cornerstone of that free exchange of energies, unconditioned by the market and by the more and more constraining pressures burdening the research of contemporary artists, which has characterised to this day the historical space of via Flaminia 58, in Rome, of which he was the president for many years. The association of artists of via Flaminia 58 – AOC F58 – has been for the past twentyfive years a place of experience and artistic research, not only for the many artists and curators who have worked there, but for all those who found in Buno Lisi’s studio an open and warm place of cultural exchange.

Bruno Lisi was born in Rome in 1942. He studied painting techniques with Alberto Ziveri at Istituto Statale d’Arte in Rome, mosaic with Michelangelo Conte and plastic art with Ettore Colla. He taught at Istituto d’Arte in l’Aquila from 1965 to 1973; at Liceo Artistico in Rome from 1973 to 1982.

Several critics and curators wrote about his work, including Carmine Benincasa, Cecilia Casorati, Patrizia Ferri, Francesco Moschini, Carla Subrizi, Claudia Terenzi, Lorenza Trucchi, Cesare Vivaldi, Marisa Volpi.

He died in Rome in 2012.

As Patrizia Ferri wrote in the catalogue of one of the artist’s exhibitions:

“From the zero grade of a perceivable absence, Lisi is able to sublimate the intrinsic and metaphorical value of the materials he uses and suggests, through frozen and extremely bright presences, both silent and enigmatic in their balance between being and nothingness, that if life today is more than ever elsewhere, the task of the artist is to bring it back here and now, colouring it with the light of tomorrow. The fascinating, silent and unreachable works by Lisi open up the way to the flight of imagination, to the deep sea of being in the empty space of infinite possibilities and of desirable worlds one can attain through art”.

(translated by Irene Ranzato)

Painting as a stimulus / Painting as vibration

As we were so used to the obstinate meticulousness of the “all full” of Bruno Lisi’s whole artistic itinerary, today it is really surprising to see him working on a new cycle that seems to have the dazzling rarefaction of the void as its foundation. To underline this apparent variation of direction of his search, he took recourse to a technique and a tool such as the ball-point pen, undoubtedly quite far from his customary predilection for a vibrant and pulsating painting, because of their being aseptic and their hinting at an indistinct and undifferentiated universe. But once again, for B. Lisi, it is a matter of giving body to unexplored depths, to bring figures subjected to tension to the surface, as if the whole work was treated in a “pictorial” way and not just the part where the sign gets thicker, clinging at and holding back the urgency of underground vibrations.

That is why removing all trace of automatism from the mark, B. Lisi imposes a sort of faded chiaro-scuro on it that lends the image that has been drawn to the surface a vitalism, an animism and a sort of panpsychism that makes his search become more related with those theories on the universe as “seething” than with pure aspiration to form.

At least this is what a certain baroque sumptuousness seems to indicate. We catch a glimpse behind those knotted and raised “curtains”, that “Ludovica Albertoni” kind of ever-changing material, stirred by the wind, but frozen by its being forced to emerge just slightly.

A skeletal presence that survived the erosion of too much void surrounding it. So it is not by chance that as soon as these presences were evoked, B. Lisi cut them out and set them in a vertical sequence to create a real stele, impressing on the whole assembly, thanks to the clearness of the two white sheets placed in succession, an intentional archaicity that immediately declares its distance from possible memories of painting-painting. All this for a more suffering interrogation on the construction of void, on the structure of the figure revealing itself as it denies itself, in the abandonment of the hand that lets go and gives body and structure without a preconceived plan.

The same dimensional exasperation impressed by the verticality of the work, that constriction to become pure poetic nook in the anomalous place on high of the various shapes, moved out of place in their most varied positions. They seem to measure the abysmal void that forces them to withdraw ever more into their shell. Then, more than a rapid passage of clouds, those apparitions seem to indicate a fear and at the same time a need to distance themselves from that void that made them emerge in the first place, in a continuous oscillation between desire to plunge in it and the fear of sinking in it. All of it in the certainty that their bursting in is guaranteed by the retreat of that void, by its opening up leaving ravines of accumulation of shadow if not of mystery.

But to underline the substantial identity between the emerging figures, reduced to simulacre or rather finds in a stratigraphic excavation, that uncontaminated void though solicited by the slight telluric shocks that set in vibration those same shreds of image, B. Lisi adds to the rarefaction of this cycle a fast sequence of more intricate signs.

A series of works where, more freely, the drawn sign superimposes itself, chases itself, intertwines with itself until it occupies every interstice. All this in a constraint to remain within the physical limits of the sheet, to not leave unexplored voids, almost to underline the distance of this mode of proceeding from going farther trustingly, from that desire to go outside the borders that was typical of J. Pollock, for example. And this enclosing inside a measured and controllable surface, making an effort to make sudden depths emerge only through the changing movements of the superimposed marks, or the discolouring of the various signs that intertwine, can only lead us to the idea that permeates B. Lisi’s work like a continual obsession from the sixties until today. This is painting intended as a continuing stimulus, a setting into vibration of the pictorial surface.

And it is this very work on the surface, paradoxically, to register that search for inner depths and great spirituality that from the historical avant-gardes onwards has always characterised the way to abstraction. And these very sheets, with their obsession for an insisted mark always turning back on itself with its own circularity, recall that naturalism, forever evoked by B. Lisi as a fundamental element of his work, in the search for that “continuum where everything is”.

Therefore it is not by chance, having underlined the distance between his work and that of the American abstract expressionism, the one that is more trusting in the “magnificent destinies and progress” of humanity, that B. Lisi tends to build a kind of logical connection with the extremely dense textures of vibrant microsigns by which M. Tobey expressed the incessant pulsating of life.

What else is that excess of full, set against that dizziness of void, if not a remote memory of that “white writing” which, aside from the basic Oriental ascent, can’t help but present itself as a cognitive moment, or better a moment of pure reflection on reality? In the same way, writing across wide, luminous surfaces, as was already done in other cycles of his paintings, is for B. Lisi like bringing up to the surface fragments of consciousness from afar that the artist struggles to catch and translate into a new order that is not the intellectualistic or conceptual one, but the more familiar one of daily life, which is a continual projection of the present.

In a sort of shadow theatre the irrepressible appearance of a universe led onto the visual stage, before it fades away, keeps us in the unstable equilibrium of precarious spectators of a scene that we would like to pass by but we are forced to continue to peep at in its disturbing and smoothed depth reminding of a Donatello bas-relief. It is this very reduction to a concentrated spatiality to mark B. Lisi’s work ever since his debut in the early sixties. Since then his moving between abstraction and figuration, searching for a result to place him outside the now worn controversy between abstractism and realism, had made him pick out from some artists such as A. Magnelli an expressive world of intense stimuli: a decisive option for an abstraction of well defined elements of solid constructive connotation. But rather than reread the theoretical contribution of that Italian master of abstractionism in a key of exasperated geometrical structuralism, as the artists of Form 1 had already done towards the end of the forties, B. Lisi captures more than the decontamination of the painting from any narrative excess, the qualities of pictorial vibration. B. Lisi privileges what in Afro will become pure luminous structure, succeeding in solving the dialectics – young as he in this period – between matter and light in a precarious equilibrium between the two terms.

The stimulus of informality after his first abstract experiences brings him to exasperate colours of mist and earth that get thicker and thicker until they turn into bituminous backgrounds that deny any visual plunge. It is in that same period that B. Lisi regains, through the monumentality of some figures, a far-reaching spatiality where the juxtaposition of ample chromatic spreads already becomes a naturalistic allusion, a forewarning of those spatial breakthroughs that, towards the end of the sixties, he will bring to masterly achievement, highlighting them in their exasperated dilation and in the forced constriction of the small format. In a kind of self-censoring exercise B. Lisi then tends to cool down whatever destructiveness the gesture of the pictorial work could hold.

The gesture, barely held back, then forces the figures caught close up – a single part of the body, two hands, with an aspiration towards the indistinct, the non specific, the non finite – to exhibit their state of fragments, as though for B. Lisi painting meant exhausting or better yet burning in a very small space and in a time that did not allow changes, much less revival, the memory of an impression. The artist then seemed to aim at stopping the speed of the passage of the image in that void meant as the true protagonist of the work rather than at fixing the image itself. Thus he reached a “physicalness” of that passage of image so that the topic slid from the objective data to their possible deformation, from the real datum to its manipulation. The pursuit of emblematical elements was founded on the search for a stringent immediateness, on the chromatic flash of lightning given as shrieked contrast of bright colours. That B. Lisi’s work would tend more and more to the reduction of any presence inside the work, stripping the flesh off the colour and eliminating all structure that could make one think of a refined complexity of planning, seems evident in later works that tend to make the void, the white of the freshly vibrating canvas, the place of minimum intervention. Something to be barely stirred, to be rippled like a wax board barely furrowed or better yet just barely crossed by meteor imprints leaving a trail that can hardly be seen.

In the end all that is left is regret for something longed and lost. Of this loss only mute and silent traces can be evoked. In becoming uniform and untouchable they stress their value of pure background figures that memory buries and digs up with obsessive insistence. That is true for the meteor-images of emphasized anatomical parts, but it is also true for the dense “tensions” elaborated by B. Lisi in the early seventies.

It is in this period that the artist begins to make a coherent criticism of the very basis of his work in order to concentrate more on its structure than on the information that it seems to want to communicate. Mind you, not in tautological terms as aniconic painting seemed to do in the same period; that is, not on the same disciplinary instruments, but rather on the foundation of vision, on those “absent structures” yet capable of determining and legitimising historically the work of art. Therefore a reduction to zero degree of painting was necessary, a rediscovery of its primary values, until pleasure of painting itself was abandoned for pure aseptic and yielding layouts. Therefore it is not by chance that B. Lisi rediscovers in the total zeroing of the Soviet avant-gardes and the formalist ones in particular, the basis of his new searches. Not only the black Square on white by K.S. Malevic, but also the stratified monochrome overlaps of A.M. Rodcenko will certainly constitute a point of reference for a new way of painting that finds in the pure spatiality of pictorial surface, not a kind of tabula rasa on which to etch and tell one’s own vision of the world, but if anything just the non objectivity of the world as sole purpose of the work, until it is demonstrated how the “practical” reality of things is not so real in the end.

All this in the name of a pure and absolute knowledge of every form of objectivity, subordinating the colour and structure of the work to a communication that is spiritual and of pure idealisation. It is worth while rereading those Tensions rather than in their aspects of ambiguity, as C. Vivaldi some time ago pointed out, in their constructive yet at the same time playful aspect, almost as patterns of the mind, remembering that constructive primordiality that as children made us play with elastic bands with our hands until we discovered complex interchangeable patterns with a simple operation of ars combinatoria. So those nearly monochrome imprints that barely furrowed the pictorial surface, until they made it vibrate from the effect of a skimming breeze, hinted at an everyday cosmology with an effect of extreme tenderness, even in their excess of concentration, if compared to the “making big” that was concealed behind the myth of the new frontier of the contemporary Cellotex by A. Burri. But what in A. Burri was a solar praise of matter brought to new beauty, in B. Lisi became a cut-out portion of an intentionally limited spatiality, reduced to its controllability and measurability. Almost to conceal, beyond any possible hedges, other spaces and other silences. This is the very aspect that B. Lisi accentuates in the mid eighties, in an ardent spiritualism that, emphasizing the centrality of the work in a kind of cosmic propagation of matter, forces it to place itself according to a truly cosmic range.

The same flowering that accompanies the sinuous unfolding of those waves of propagation, seems to highlight the magical act of creating. Nothing more distant in this focusing – almost under a microscope – than D. Gnoli’s “close up” shots that emphasize reality in order to exorcise it. In these measured levitations it is as if the matter fermented, leaving luminous trails and a precipitation of fine dust. That precipitation has the alchemic flavour of transmutation of matter and is certainly the sign of the loving support that B. Lisi, with his maieutic action, seems to give the matter itself. He almost forces it to show off its dazzling beauty with its enamel and its incisiveness, although aware that it inevitably takes the signs of its own destruction with itself. Thus the same glossy beauty seems to be the common element of the most recent works. Starting in 1986, B. Lisi created a cycle of blue paintings extraordinarily linked together in a thrilling range.

In the first series, a sort of framing, a proscenium created with a unitary border on the canvas, made the magmatic explosion of cluts of various sizes of matter burst onto a sort of ideal forestage. Yet at the same time the exasperated frontality of everything hinted at a frozen Böcklinian Island of the Dead barely eaten into by corrosion and by the impetuousness of those waves or – which is the same thing – by the uncontrolled thickening of an aggressive vegetation. And yet the final effect restored the same pitiless hardness of a desert landscape by C.D. Friedrich that, only more recently, began to soften itself in B. Lisi’s latest works, the “millimetred” series of landscapes juxtaposed like tesseras in an ideal mosaic.

Here is the unfolding in all its vitality of the artist’s passion for frescoes that for several years he was able to get acquainted with as a restorer. And as a succession of days can also be intended the assembly of those chain links where the matter expands, spreads out and is emphasized as if to state that its beauty can be at least fixed by the love for things. Even when one discovers in them and reveals simultaneously and wickedly the unfathomable void we could fall into if we were content with that extenuating “whitened tomb” kind of beauty and if that eternal reaching out for elsewhere did not support us.

Francesco Moschini

text in the catalogue

of the anthological exhibition at Palazzo Brancaccio

26/11/2001-26/2/2002

translated by Helen Pringle